Introduction

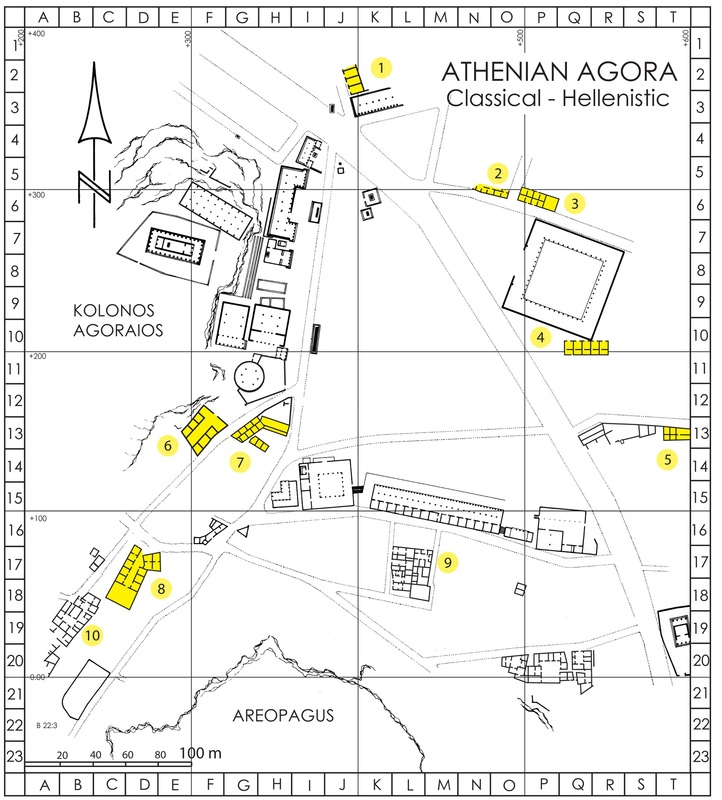

The commercial buildings in the Area of the Agora are scattered in areas neighboring the civic administrative structures, easily accessible from the centre of the Agora but – at the same time- distinctively separate, placed at the borders of the Agora. The examples discussed here, suggest that different types of commercial activity was taking place in specific areas of the Agora, while the archaeological evidence from these buildings also shows a variety of occupational uses for these buildings.

Neatline Presentation can be accessed here: http://neatline.dukewired.org/neatline/show/commericial-buildings-in-the-agora

The commercial buildings in the Area of the Agora are scattered in areas neighboring the civic administrative structures, easily accessible from the centre of the Agora but – at the same time- distinctively separate, placed at the borders of the Agora. The examples discussed here, suggest that different types of commercial activity was taking place in specific areas of the Agora, while the archaeological evidence from these buildings also shows a variety of occupational uses for these buildings.

Neatline Presentation can be accessed here: http://neatline.dukewired.org/neatline/show/commericial-buildings-in-the-agora

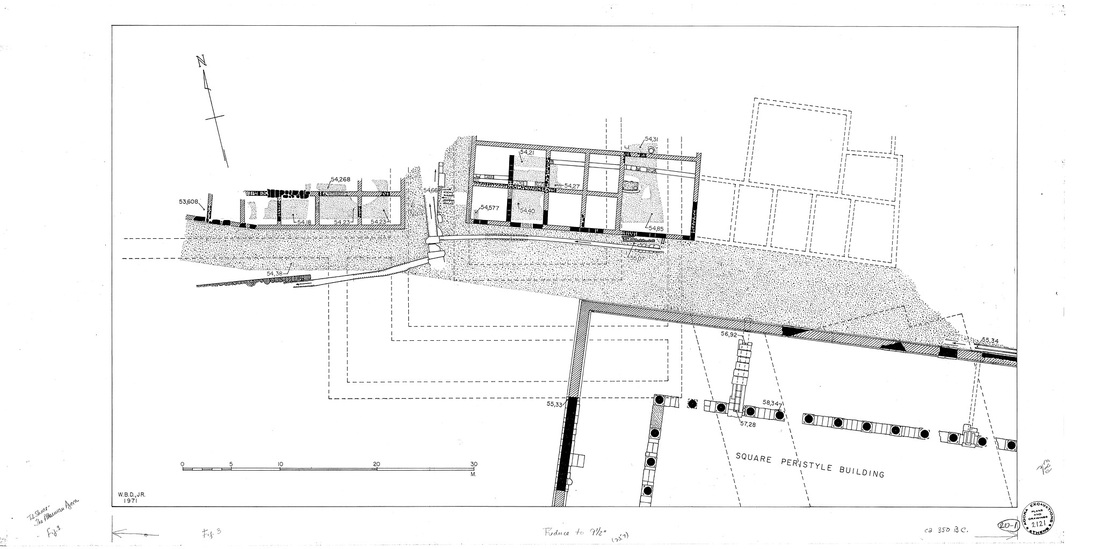

South of the Agora Square

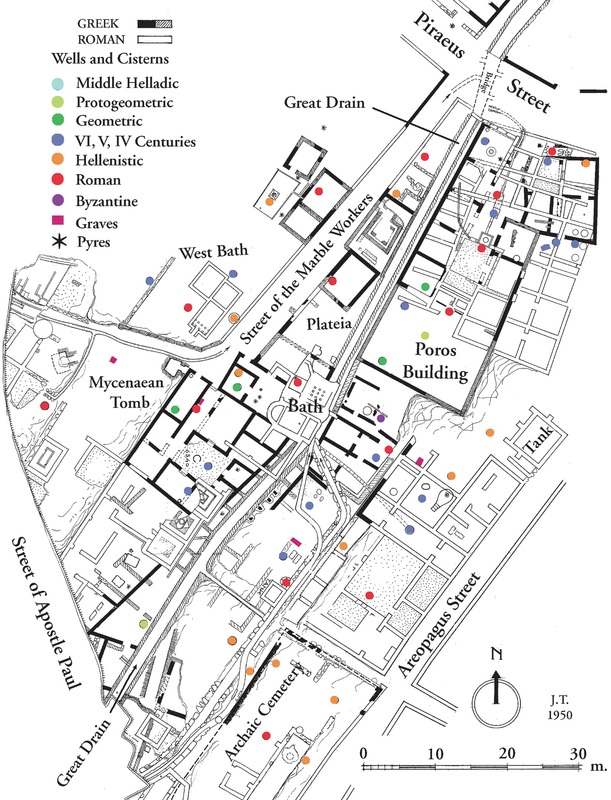

Rotroff has argued on the basis of the discovery of pyres dating to the 4th century and the similarity of the plan to other known commercial structures that the Poros Building was a workshop, probably from the beginning of its use (Rotroff 1999, 44- 45). The discovery of marble chips in the northwest corner, the northern corridor and the annex suggest that it housed marble workers. Rotroff has fixed the dating of this activity to the second phase of the building, extending no further than the 4th century. Certainly, the existence of the marble workers can be seen as connected to the proximity of the Poros to the Street of the Marble Workers.

- The Poros Building

Rotroff has argued on the basis of the discovery of pyres dating to the 4th century and the similarity of the plan to other known commercial structures that the Poros Building was a workshop, probably from the beginning of its use (Rotroff 1999, 44- 45). The discovery of marble chips in the northwest corner, the northern corridor and the annex suggest that it housed marble workers. Rotroff has fixed the dating of this activity to the second phase of the building, extending no further than the 4th century. Certainly, the existence of the marble workers can be seen as connected to the proximity of the Poros to the Street of the Marble Workers.

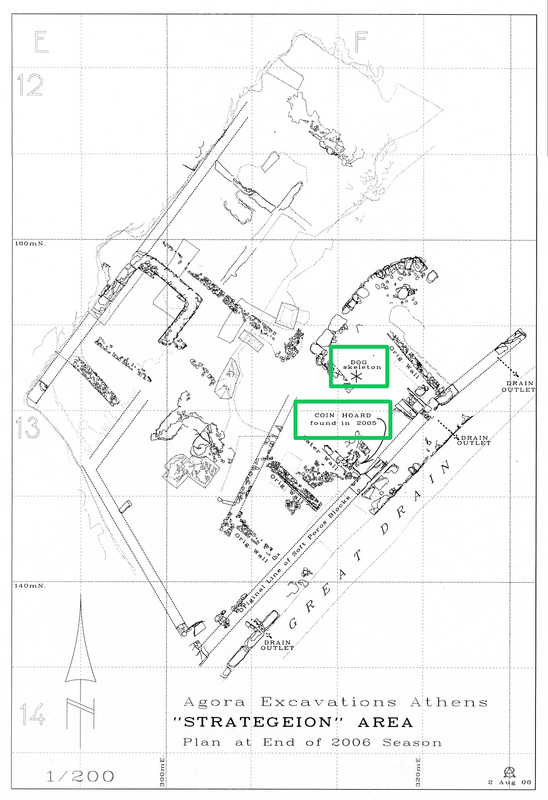

2. Strategeion

The Strategeion is another case of a building that has attracted scholarly attention, specifically concerning its function. Recently it was excavated again (2003- 2005), prompting new discussions (outlined in the introductory section of this website). It was erected between 440- 430 BCE and it was possibly destroyed by Sulla in 86 AD, as the pottery deposits suggest.

Rotroff (2013) describes in detail its plan:

The building was roughly trapezoidal, with rows of rooms on its northwestern and southeastern sides (apparently three on the northwest, four on thesoutheast), a corridor between them, and a forecourt to the northeast. It was served by a cistern system and a well and drained by five drains leading into the Great Drain to the east (some at least are not part of the original plan). (Rotroff 2013, 126)

The Strategeion is another case of a building that has attracted scholarly attention, specifically concerning its function. Recently it was excavated again (2003- 2005), prompting new discussions (outlined in the introductory section of this website). It was erected between 440- 430 BCE and it was possibly destroyed by Sulla in 86 AD, as the pottery deposits suggest.

Rotroff (2013) describes in detail its plan:

The building was roughly trapezoidal, with rows of rooms on its northwestern and southeastern sides (apparently three on the northwest, four on thesoutheast), a corridor between them, and a forecourt to the northeast. It was served by a cistern system and a well and drained by five drains leading into the Great Drain to the east (some at least are not part of the original plan). (Rotroff 2013, 126)

North of the Agora Square

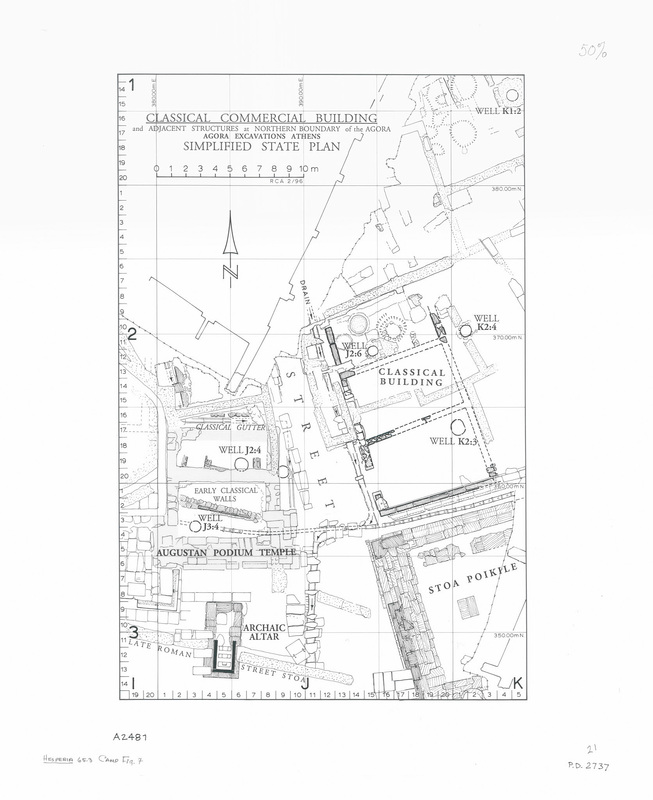

3. Classical Commercial Building

This is a structure that is still being excavated, so there is still no finalized study of the chronology of the different rooms and finds excavated. The plan of the building is not finalized but so far it doesn't exhibit the common characteristics of commercial architecture such as the courtyard and the corridor. Camp has suggested that it was built piecemeal (Camp 2003, 249), an interesting juxtaposition to the monumental poros structures in the south of the Agora. Notably, ten layers were excavated in the southern room dating to the first century, but the excavation to the rest of the rooms is ongoing.

There is a great variety of material remains characterizing the results of the excavations, indicating that different workshops were housed in the building. However, there has been no concise study of the archaeological findings in regards to the possible professions they could indicate. Rotroff reviews the results of the discoveries until 2001:

There is abundant evidence of industrial activity. Room 1: shallow pits

containing iron and bronze slag, patches of pigment on floors, terracotta

molds, a Y-shaped drain in the original floor, and, in the 3rd century, marble

dust and chips (Shear 1984, p. 45), as well as fragments of lead and pumice

in the floor makeup. Room 2: clay impression of metal vessel (Camp 1999,

pp. 277–278, no. 50, fig. 27). Room 3: shell containing pigment. Room

4: marble dust(?), pigment, figurine mold (T 4893). Rooms 5 and 6: iron

slag. Room 7: iron slag and shells containing red and yellow pigment

(BI 1290, BI 1291).

Finally, Camp notices in the 2009 Preliminary Excavation Report that this building contains the highest concentration of pyres, suggestive of its continuous occupation.

3. Classical Commercial Building

This is a structure that is still being excavated, so there is still no finalized study of the chronology of the different rooms and finds excavated. The plan of the building is not finalized but so far it doesn't exhibit the common characteristics of commercial architecture such as the courtyard and the corridor. Camp has suggested that it was built piecemeal (Camp 2003, 249), an interesting juxtaposition to the monumental poros structures in the south of the Agora. Notably, ten layers were excavated in the southern room dating to the first century, but the excavation to the rest of the rooms is ongoing.

There is a great variety of material remains characterizing the results of the excavations, indicating that different workshops were housed in the building. However, there has been no concise study of the archaeological findings in regards to the possible professions they could indicate. Rotroff reviews the results of the discoveries until 2001:

There is abundant evidence of industrial activity. Room 1: shallow pits

containing iron and bronze slag, patches of pigment on floors, terracotta

molds, a Y-shaped drain in the original floor, and, in the 3rd century, marble

dust and chips (Shear 1984, p. 45), as well as fragments of lead and pumice

in the floor makeup. Room 2: clay impression of metal vessel (Camp 1999,

pp. 277–278, no. 50, fig. 27). Room 3: shell containing pigment. Room

4: marble dust(?), pigment, figurine mold (T 4893). Rooms 5 and 6: iron

slag. Room 7: iron slag and shells containing red and yellow pigment

(BI 1290, BI 1291).

Finally, Camp notices in the 2009 Preliminary Excavation Report that this building contains the highest concentration of pyres, suggestive of its continuous occupation.

4. Greek Building Δ

Chronology:

1. 480 BCE – early 3rd century BCE

2. early 3rd century BCE - 175 BCE or later(abandonment)

3. 125 BCE – 86 BCE

4. 86 BCE - 2nd century AD

It consisted of two rows of eight same- sized rooms, placed in two rows and located westwards from a courtyard. The courtyard would have been accessible form two points: the street on the south and the southwest room. Milbank (90) ascertains that this is evidence that the courtyard also had a use for the merchants. The same author describes the arrangement of the space in the shops: two adjoined rooms would make up a store, as the evidence in the west end of the building suggests. Another suggestion is that the extend of the remodeling that is evident on the buildings floors could point to a construction that changes constantly in order to accommodate new shops. Also, the building is though to have been one- storied (coming to opposition with the multi- storied Classical Commercial Building).

The Greek Building Δ is thought to have housed merchants, shopkeepers and artisans. Milbank supports that there is enough evidence to suggest the existence of two commercial activities: “a retail enterprise specializing in foodstuffs, operated in a single room establishment during the late fourth century” and “an industrial enterprise specializing in the production of metal vessels, operated in a two- roomed establishment during the second century B.C.” (104).

Chronology:

1. 480 BCE – early 3rd century BCE

2. early 3rd century BCE - 175 BCE or later(abandonment)

3. 125 BCE – 86 BCE

4. 86 BCE - 2nd century AD

It consisted of two rows of eight same- sized rooms, placed in two rows and located westwards from a courtyard. The courtyard would have been accessible form two points: the street on the south and the southwest room. Milbank (90) ascertains that this is evidence that the courtyard also had a use for the merchants. The same author describes the arrangement of the space in the shops: two adjoined rooms would make up a store, as the evidence in the west end of the building suggests. Another suggestion is that the extend of the remodeling that is evident on the buildings floors could point to a construction that changes constantly in order to accommodate new shops. Also, the building is though to have been one- storied (coming to opposition with the multi- storied Classical Commercial Building).

The Greek Building Δ is thought to have housed merchants, shopkeepers and artisans. Milbank supports that there is enough evidence to suggest the existence of two commercial activities: “a retail enterprise specializing in foodstuffs, operated in a single room establishment during the late fourth century” and “an industrial enterprise specializing in the production of metal vessels, operated in a two- roomed establishment during the second century B.C.” (104).

Sources:

Camp, J. McK., II. 2003. “Excavations in the Athenian Agora: 1998–2001,” Hesperia 72, pp. 241– 280.

———. 2007. “Excavations in the Athenian Agora: 2002–2007,” Hesperia 76, pp. 627–663.

Crosby, M. 1951. “The Poros Building,” in R. S. Young, “An Industrial District of Ancient Athens,” Hesperia 20, pp. 168–187.

Milbank, T. L. 2002. “A Commercial and Industrial Building in the Athenian Agora, 480 BC. to A.D. 125” (diss. Bryn Mawr College).

Rotroff, Susan. 2009. “Commerce and Crafts around the Athenian Agora,” in The

Athenian Agora: New Perspectives on an Ancient Site, ed. J. McK. Camp II and C. A. Mauzy, Mainz, pp. 39–46.

———.2013. Industrial Religion: the saucer pyres of the Athenian Agora, Princeton.

Camp, J. McK., II. 2003. “Excavations in the Athenian Agora: 1998–2001,” Hesperia 72, pp. 241– 280.

———. 2007. “Excavations in the Athenian Agora: 2002–2007,” Hesperia 76, pp. 627–663.

Crosby, M. 1951. “The Poros Building,” in R. S. Young, “An Industrial District of Ancient Athens,” Hesperia 20, pp. 168–187.

Milbank, T. L. 2002. “A Commercial and Industrial Building in the Athenian Agora, 480 BC. to A.D. 125” (diss. Bryn Mawr College).

Rotroff, Susan. 2009. “Commerce and Crafts around the Athenian Agora,” in The

Athenian Agora: New Perspectives on an Ancient Site, ed. J. McK. Camp II and C. A. Mauzy, Mainz, pp. 39–46.

———.2013. Industrial Religion: the saucer pyres of the Athenian Agora, Princeton.