what do we mean by 'workshop?'

Eleni Hasaki, in “Ceramic Kilns of Ancient Greece,” provides a clear and outlined definition of what constituted a workshop in the ancient world. Beginning with a study of kilns in “semi-isolation,” Hasaki moves on to establish them within their natural context-- a pottery workshop. “A workshop is: ‘a room, apartment, or building in which manual or industrial work is carried on.’ This definition has two major components: a) the structure itself (size is not important, but the areas must be well defined and closed off architecturally) b) the activity conducted inside this structure” (252). Importantly, Hasaki notes that the work conducted in a workshop is regular and organized industry, rather than part-time production. There are also difficulties in understanding the semantics and functions of these types of spaces. For example, ancient sources indicate three generic terms for workshop—one being any workshops in an artisanal area (sculpture, perfume, etc), even including brothels; a second, which doesn’t indicate whether domestic or non-domestic space is referred to (as a workshop can be near or within the boundaries of a house); a third acts as the most generic term for a ceramic workshop (which becomes complicated when we understand how different ceramic workshops can be, in terms of scale and production). Additionally, Hasaki presents the necessary features in identifying a workshop. Perhaps most frustrating is that architectural evidence, while important for definition, proves now to be unhelpful in the identification process. Isolated (and mobile) factors like benches, disks, or drainage systems cannot alone identify the locale (258). Identification relies upon a combination of permanent features (kiln, installations for potter’s wheel, clay settling basins) and movable features (raw material, pottery, technical equipment) (260).

Sources:

Hasaki, E. 2002, Ceramic Kilns in Ancient Greece: Technology and Organization of Ceramic Workshops, Dissertation: University of Cincinnati.

Sources:

Hasaki, E. 2002, Ceramic Kilns in Ancient Greece: Technology and Organization of Ceramic Workshops, Dissertation: University of Cincinnati.

Limitations and fundamentals

Very few iconographic instances indicate interior space or separation of covered/semi-covered space of a workshop. There are no documents that record an dimensions of these ancient workshops. We know that store rooms and drying floors would have existed, but nothing of the spatial relationship (14). Additionally, few workshops have been entirely excavated--kilns are recovered largely during salvage excavations. Settling basins and kilns are the safest identification criteria (24). The average diameter of a kiln is 1.10-1.50 meters. We should not think of large storage areas in these manufacturing sites--raw materials would have been acquired as needed; stored jars general indicate a retail site (26). Most of the workshops in the Mediterranean would have likely been small, full time, and family-based.

source:

Hasaki, Eleni. "Crafting Spaces." Pottery in the Archaeological Record: Greece and Beyond: Acts of the International Colloquium Held at the Danish and Canadian Institutes in Athens, June 20-22, 2008. Ed. Mark L. Lawall and John Lund. 12-28. Print.

source:

Hasaki, Eleni. "Crafting Spaces." Pottery in the Archaeological Record: Greece and Beyond: Acts of the International Colloquium Held at the Danish and Canadian Institutes in Athens, June 20-22, 2008. Ed. Mark L. Lawall and John Lund. 12-28. Print.

Production and ideology

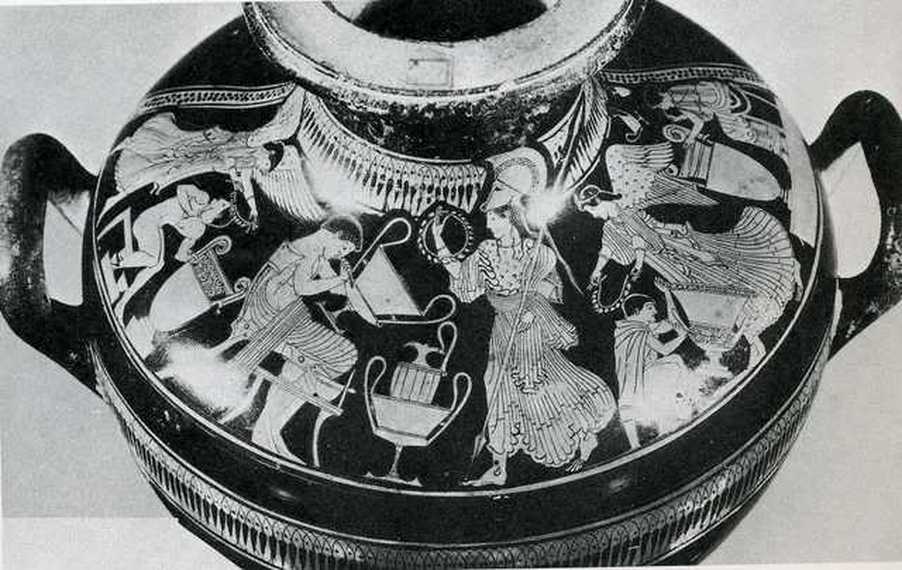

In her article on commercial buildings in the Agora, Susan Rotroff accounts for the role of religion in industrial practices. The floors have revealed collections of drinking cups, lamps, miniature saucers, and cooking pots along with animal bones. These 'saucer-pyres' indicate these deposits as being remains of sacrifice. While the function of these deposits is unknown, they are most prevalently found in buildings related with industry and craft. To quote, "a craftsman would have good reason to seek the favor of the gods. He needed their help to insure the success of the often complex and unpredictable industrial processes upon which his livelihood depended. His work could be dangerous and he needed their protection to insure his personal safety" (Rotroff 43). (For more on commercial buildings in the Agora click here) In Ceramicus Redivivus, "The Material and Its Interpretation," John Papadopoulos supplements this argument, particularly as it relates to ceramic workshops. The language of the ancient poem Kiln emphasizes the superstitious elements of pottery firing. Certain iconographies (ithyphallic satyr and daemons) relate to the warding off of evils that may 'befall the pottery during firing' (196). The plaques dedicated to the god Poseidon at Penteskouphia depict the craftsmen at the moment of tending the kiln--the part of the process that need the most divine help. Below, in the setting of an ideal workshop, Athena crowns the master potter, flanked by two male assistants. A woman, "potter-painter's wife," sits in the corner (see detail). In other iconographies, Athena looks on, rather than actively interacting, overseeing the activity.

Sources:

Rotroff, Susan. "Commerce and Crafts Around the Athenian Agora." The Athenian Agora: New Perspectives on an Ancient Site. Ed. John McK. Camp and Craig A. Mauzy. Mainz Am Rhein: Verlag Philipp Von Zabern, 2009. 39-46. Print.

Papadopoulos, John K. Ceramicus Redivivus: The Early Iron Age Potters' Field in the Area of the Classical Athenian Agora. Princeton, NJ: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2003. Print.

Sources:

Rotroff, Susan. "Commerce and Crafts Around the Athenian Agora." The Athenian Agora: New Perspectives on an Ancient Site. Ed. John McK. Camp and Craig A. Mauzy. Mainz Am Rhein: Verlag Philipp Von Zabern, 2009. 39-46. Print.

Papadopoulos, John K. Ceramicus Redivivus: The Early Iron Age Potters' Field in the Area of the Classical Athenian Agora. Princeton, NJ: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2003. Print.